COMMENTARY

Commentary

Commentary

1. Globalization’s hollowing out of the working class is reflected in the depiction of aging blue collar fathers whose physical labor involves (pointedly) the construction of homes. Faced with work-related injuries that variously leave them unemployed or dealing with chronic medical conditions that require prohibitively expensive treatments, these characters struggle with neoliberal corporate insurance policies and state welfare directives that make it hard for them to claim legitimate benefits, even as they come to terms with bodies that have become frail that were once robust.

2. Working-class fathers must grapple with the contradiction between their loss of status and work opportunities in a world transformed by neoliberal globalization and the symbolic authority traditionally conferred upon but also demanded or expected of them as the sole breadwinner and head of the family. This split sense of fatherhood is dramatized in films through characters who fail as fathers in real life but who feel compelled to perform fatherhood as figures of authority, whether out in society or in one’s fantasies.

6. The difficulties in raising a family are compounded by institutional structures and frameworks – whether corporate or bureaucratic – whose representatives in charge of mortgage loans, insurance claims, and welfare benefits are depicted to function as gatekeepers rather than enablers. Enforcing the system’s rules extends to the agents of law and order who rely on policing and surveillance to contain social problems by detaining and punishing offenders as a way to deter others and prevent further infractions or abuse, but the system is frequently unjust and blind or indifferent to suffering.

8. The patriarchal ideology that went hand in hand with the centrality of the nuclear family during a developing society’s industrial phase of modernization haunts its now decaying and dilapidated spaces. The dream of an ideal home or family that a blue collar father returns to after a hard day’s work – a supportive wife handling the domestic chores, obedient children doing their homework – has become so antiquated that it appears like a ghostly afterimage, as dead as the authoritarian leaders who presided over such periods of economic takeoff but refusing to vanish.

9. The return of the repressed comes in the form of an attempt at overcompensating for the loss of agency and sense of impotence to the working-class father by reasserting his manhood through an act of violence within the family, an instance of so-called “toxic masculinity.” Such acts of domestic violence directed towards the spouse or children are depicted as deadly and contagious: not only is killing within the family portrayed but they are seen to extend outwards into society as instances of violence across gender, generational, and class lines.

CODA. The free individual serving as the bedrock or underpinnings of a liberal society – a notion that neoliberal and libertarian ideologies take to an extreme – is called into question when it comes into contradiction with the demands of family and community. The mythical figure of the cowboy representing the rugged and resourceful individual who roams the frontier but is forever denied a place as a true member of the home, family, or community haunts the American imagination. The refusal of the communal or collective has profound ideological effects on the disenfranchised.

3. Stories of single moms resorting to sex work to provide for their kids are emblematic of the difficulties in parenting under an economically punishing ideology that moreover atomizes the family and stigmatizes the collective in the name of individual freedom and enterprise. According to neoliberalism, aging working-class women who lose their homes or are terminally ill needing costly medical care hit the road out of choice rather than necessity. Meanwhile, the traditional wife and mother who stays at home has become an anachronism for economic and ideological reasons.

4. The children that we see in films from the age of inequality are latchkey kids with a difference: no real home exists for them and often they are fending for themselves somewhere out in the wild or in public places. Their tenuous relationship to home as a physical space is further stressed through their exposure to processes like foreclosures and forced evictions that leave as their playgrounds abandoned homes or redevelopment sites testifying to both the housing collapse in 2008 and the real estate bubble that preceded it.

5. With the financialization of housing, homes lose their practical function and meaning as dwellings that provide a place of abode for working families, becoming instead a commodity for investment and speculation. As property prices skyrocket and affordability becomes out of reach, construction sites or show apartments for luxury homes come to represent an unrealizable dream in films where the characters are unemployed or eke out a precarious living as day laborers and even human billboards. Squatters find themselves in dilapidated spaces so sad the walls are streaked in tears.

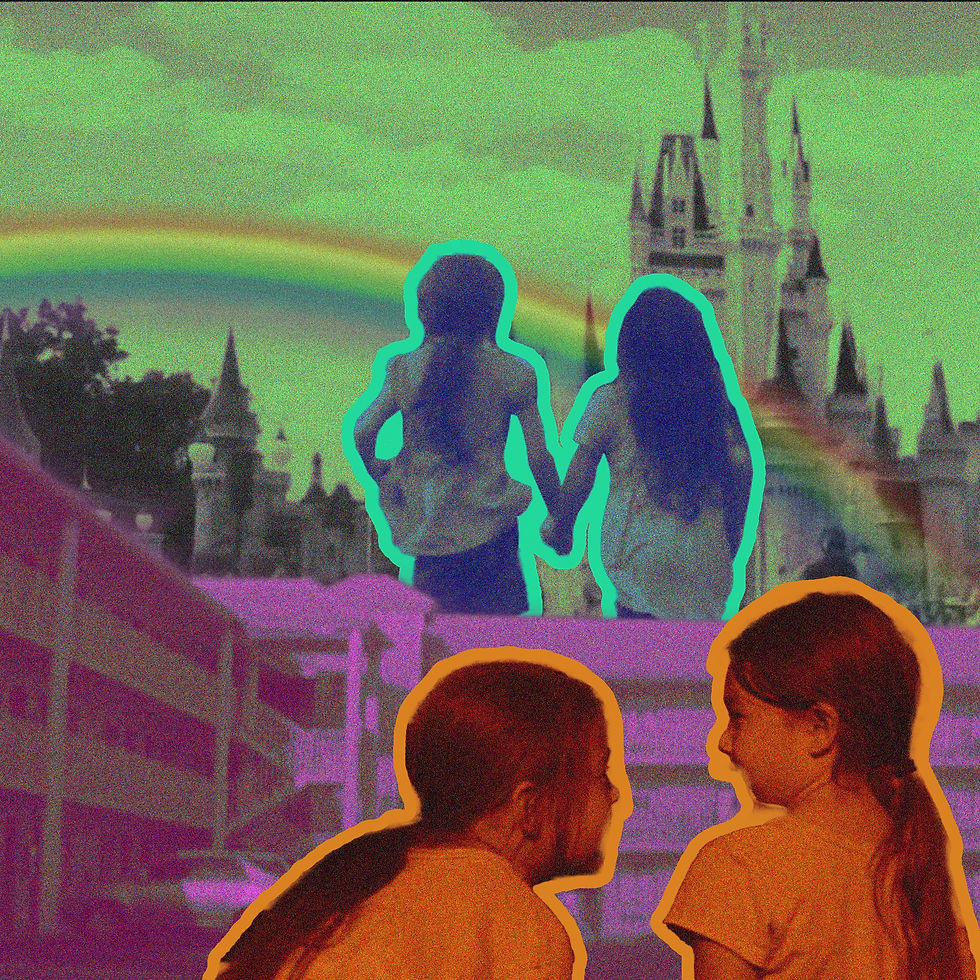

7. “Cruel optimism” may be a burden carried disproportionately by Americans for whom the dream or myth of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” looms larger than reality itself. Only there can you find the Magic Kingdom or Route 66. The play in size and proportions is telling: huge mythical landscapes that represent “America” dwarf characters who paradoxically aspire to the scale of the idea’s greatness. The irony? Characters who can’t afford a car making their way on foot like ants next to super-sized, sign-like architecture designed to be seen from an automobile.

10. The fractious society that we find ourselves in today is also remarkably violent and confrontational. Its disharmony stems from extreme inequalities produced by societal shifts that were engineered politically. The very real and negative effects this has had on those who lost out in the process of transition can act like a boomerang. The resentment that is built up on the level of the individual spills over into violence against oneself and others, while antagonisms within the family extend out into society taking the form of mass protest and civil unrest.

3. Stories of single moms resorting to sex work to provide for their kids are emblematic of the difficulties in parenting under an economically punishing ideology that moreover atomizes the family and stigmatizes the collective in the name of individual freedom and enterprise. According to neoliberalism, aging working-class women who lose their homes or are terminally ill needing costly medical care hit the road out of choice rather than necessity. Meanwhile, the traditional wife and mother who stays at home has become an anachronism for economic and ideological reasons.

4. The children that we see in films from the age of inequality are latchkey kids with a difference: no real home exists for them and often they are fending for themselves somewhere out in the wild or in public places. Their tenuous relationship to home as a physical space is further stressed through their exposure to processes like foreclosures and forced evictions that leave as their playgrounds abandoned homes or redevelopment sites testifying to both the housing collapse in 2008 and the real estate bubble that preceded it.

5. With the financialization of housing, homes lose their practical function and meaning as dwellings that provide a place of abode for working families, becoming instead a commodity for investment and speculation. As property prices skyrocket and affordability becomes out of reach, construction sites or show apartments for luxury homes come to represent an unrealizable dream in films where the characters are unemployed or eke out a precarious living as day laborers and even human billboards. Squatters find themselves in dilapidated spaces so sad the walls are streaked in tears.

7. “Cruel optimism” may be a burden carried disproportionately by Americans for whom the dream or myth of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” looms larger than reality itself. Only there can you find the Magic Kingdom or Route 66. The play in size and proportions is telling: huge mythical landscapes that represent “America” dwarf characters who paradoxically aspire to the scale of the idea’s greatness. The irony? Characters who can’t afford a car making their way on foot like ants next to super-sized, sign-like architecture designed to be seen from an automobile.

10. The fractious society that we find ourselves in today is also remarkably violent and confrontational. Its disharmony stems from extreme inequalities produced by societal shifts that were engineered politically. The very real and negative effects this has had on those who lost out in the process of transition can act like a boomerang. The resentment that is built up on the level of the individual spills over into violence against oneself and others, while antagonisms within the family extend out into society taking the form of mass protest and civil unrest.

CODA. The free individual serving as the bedrock or underpinnings of a liberal society – a notion that neoliberal and libertarian ideologies take to an extreme – is called into question when it comes into contradiction with the demands of family and community. The mythical figure of the cowboy representing the rugged and resourceful individual who roams the frontier but is forever denied a place as a true member of the home, family, or community haunts the American imagination. The refusal of the communal or collective has profound ideological effects on the disenfranchised.

1. Globalization’s hollowing out of the working class is reflected in the depiction of aging blue collar fathers whose physical labor involves (pointedly) the construction of homes. Faced with work-related injuries that variously leave them unemployed or dealing with chronic medical conditions that require prohibitively expensive treatments, these characters struggle with neoliberal corporate insurance policies and state welfare directives that make it hard for them to claim legitimate benefits, even as they come to terms with bodies that have become frail that were once robust.

2. Working-class fathers must grapple with the contradiction between their loss of status and work opportunities in a world transformed by neoliberal globalization and the symbolic authority traditionally conferred upon but also demanded or expected of them as the sole breadwinner and head of the family. This split sense of fatherhood is dramatized in films through characters who fail as fathers in real life but who feel compelled to perform fatherhood as figures of authority, whether out in society or in one’s fantasies.

6. The difficulties in raising a family are compounded by institutional structures and frameworks – whether corporate or bureaucratic – whose representatives in charge of mortgage loans, insurance claims, and welfare benefits are depicted to function as gatekeepers rather than enablers. Enforcing the system’s rules extends to the agents of law and order who rely on policing and surveillance to contain social problems by detaining and punishing offenders as a way to deter others and prevent further infractions or abuse, but the system is frequently unjust and blind or indifferent to suffering.

8. The patriarchal ideology that went hand in hand with the centrality of the nuclear family during a developing society’s industrial phase of modernization haunts its now decaying and dilapidated spaces. The dream of an ideal home or family that a blue collar father returns to after a hard day’s work – a supportive wife handling the domestic chores, obedient children doing their homework – has become so antiquated that it appears like a ghostly afterimage, as dead as the authoritarian leaders who presided over such periods of economic takeoff but refusing to vanish.

9. The return of the repressed comes in the form of an attempt at overcompensating for the loss of agency and sense of impotence to the working-class father by reasserting his manhood through an act of violence within the family, an instance of so-called “toxic masculinity.” Such acts of domestic violence directed towards the spouse or children are depicted as deadly and contagious: not only is killing within the family portrayed but they are seen to extend outwards into society as instances of violence across gender, generational, and class lines.

1. Globalization’s hollowing out of the working class is reflected in the depiction of aging blue collar fathers whose physical labor involves (pointedly) the construction of homes. Faced with work-related injuries that variously leave them unemployed or dealing with chronic medical conditions that require prohibitively expensive treatments, these characters struggle with neoliberal corporate insurance policies and state welfare directives that make it hard for them to claim legitimate benefits, even as they come to terms with bodies that have become frail that were once robust.

1. Globalization’s hollowing out of the working class is reflected in the depiction of aging blue collar fathers whose physical labor involves (pointedly) the construction of homes. Faced with work-related injuries that variously leave them unemployed or dealing with chronic medical conditions that require prohibitively expensive treatments, these characters struggle with neoliberal corporate insurance policies and state welfare directives that make it hard for them to claim legitimate benefits, even as they come to terms with bodies that have become frail that were once robust.

2. Working-class fathers must grapple with the contradiction between their loss of status and work opportunities in a world transformed by neoliberal globalization and the symbolic authority traditionally conferred upon but also demanded or expected of them as the sole breadwinner and head of the family. This split sense of fatherhood is dramatized in films through characters who fail as fathers in real life but who feel compelled to perform fatherhood as figures of authority, whether out in society or in one’s fantasies.

3. Stories of single moms resorting to sex work to provide for their kids are emblematic of the difficulties in parenting under an economically punishing ideology that moreover atomizes the family and stigmatizes the collective in the name of individual freedom and enterprise. According to neoliberalism, aging working-class women who lose their homes or are terminally ill needing costly medical care hit the road out of choice rather than necessity. Meanwhile, the traditional wife and mother who stays at home has become an anachronism for economic and ideological reasons.

4. The children that we see in films from the age of inequality are latchkey kids with a difference: no real home exists for them and often they are fending for themselves somewhere out in the wild or in public places. Their tenuous relationship to home as a physical space is further stressed through their exposure to processes like foreclosures and forced evictions that leave as their playgrounds abandoned homes or redevelopment sites testifying to both the housing collapse in 2008 and the real estate bubble that preceded it.

5. With the financialization of housing, homes lose their practical function and meaning as dwellings that provide a place of abode for working families, becoming instead a commodity for investment and speculation. As property prices skyrocket and affordability becomes out of reach, construction sites or show apartments for luxury homes come to represent an unrealizable dream in films where the characters are unemployed or eke out a precarious living as day laborers and even human billboards. Squatters find themselves in dilapidated spaces so sad the walls are streaked in tears.

6. The difficulties in raising a family are compounded by institutional structures and frameworks – whether corporate or bureaucratic – whose representatives in charge of mortgage loans, insurance claims, and welfare benefits are depicted to function as gatekeepers rather than enablers. Enforcing the system’s rules extends to the agents of law and order who rely on policing and surveillance to contain social problems by detaining and punishing offenders as a way to deter others and prevent further infractions or abuse, but the system is frequently unjust and blind or indifferent to suffering.

7. “Cruel optimism” may be a burden carried disproportionately by Americans for whom the dream or myth of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” looms larger than reality itself. Only there can you find the Magic Kingdom or Route 66. The play in size and proportions is telling: huge mythical landscapes that represent “America” dwarf characters who paradoxically aspire to the scale of the idea’s greatness. The irony? Characters who can’t afford a car making their way on foot like ants next to super-sized, sign-like architecture designed to be seen from an automobile.

8. The patriarchal ideology that went hand in hand with the centrality of the nuclear family during a developing society’s industrial phase of modernization haunts its now decaying and dilapidated spaces. The dream of an ideal home or family that a blue collar father returns to after a hard day’s work – a supportive wife handling the domestic chores, obedient children doing their homework – has become so antiquated that it appears like a ghostly afterimage, as dead as the authoritarian leaders who presided over such periods of economic takeoff but refusing to vanish.

9. The return of the repressed comes in the form of an attempt at overcompensating for the loss of agency and sense of impotence to the working-class father by reasserting his manhood through an act of violence within the family, an instance of so-called “toxic masculinity.” Such acts of domestic violence directed towards the spouse or children are depicted as deadly and contagious: not only is killing within the family portrayed but they are seen to extend outwards into society as instances of violence across gender, generational, and class lines.

10. The fractious society that we find ourselves in today is also remarkably violent and confrontational. Its disharmony stems from extreme inequalities produced by societal shifts that were engineered politically. The very real and negative effects this has had on those who lost out in the process of transition can act like a boomerang. The resentment that is built up on the level of the individual spills over into violence against oneself and others, while antagonisms within the family extend out into society taking the form of mass protest and civil unrest.